Of Myths and Questions

There is a certain magic created when a successful book is picked up for a blockbuster movie and set in a picture-perfect location where visitors can roam and admire and stand in the footsteps of their literary heroes. To immerse ourselves in something grand that carries a mystique of history or art is irresistible. Plus, we all like a healthy dose of mythmaking, don’t we?

Jim Williams was the man responsible for a grand renovation of this Italianate-style home after he purchased it in 1969. He was one of Savannah’s first and most prolific restorationists, having restored over fifty homes in the area and saving them from the horrible fate of becoming a paved parking lot. (Hence, Williams may be the source of Savannah’s legendary parking challenges.)

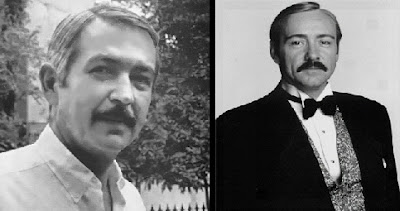

Williams was also the main character of John Berendt’s non-fiction tome, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, short-listed for the Pulitzer Prize and made into a movie starring Kevin Spacey as a shorter version of Mr. Williams. The Mercer family name comes from the grandfather of Johnny Mercer, the singer. The grandfather only began the initial design of the house and dug the foundation before he volunteered for the Confederacy.

By the time Mr. Williams purchased the house it had been vacant many years after the Shriners abandoned it as their primary office. So, it was left to Mr. Williams to bring the house to life. He did so with great attention to detail and cleverness, including wallpaper in the bathroom in the design of a cane back chair that changes color from red and gold to red and green when light shines upon it.

Mr. Williams’ clever personality is a source of many stories. He was an antique dealer at an early age who loved old stuff but not to the point that he cherished it above all else. His cat supposedly dug its claws into a couch and chewed the ears of a leopard skin from Africa to which Jim Williams yawned. “What good is nice stuff if you can’t live among it,” he was believed to have said in response.

I finally visited the Mercer Williams house on a recent trip to Savannah. The Berendt book is a favorite of mine for two reasons. First, the opening line – “He was tall, about fifty, with darkly handsome, almost sinister features: a neatly trimmed mustache, hair turning silver at the temples, and eyes so black they were like the tinted windows of a sleek limousine—he could see out, but you couldn’t see in.” So great.

The second reason is the concept that the author evokes of a city having a question. “If you go to Atlanta, the first question people ask you is what’s your business?” In Macon, they ask, “Where do you go to church?” In Augusta, they ask your grandmother’s maiden name. But in Savannah, the first question people ask you is “What would you like to drink?”

I have often bantered over cocktails about what the question might be for particular cities. In Washington, D.C., the question would be “What do you do?” or “Who do you work for?” Work and power being this city’s two primary drivers. In New York, the question must be “Who are you wearing?” and so forth. The question that epitomizes a setting, its people, and its culture is intriguing. So often have I repeated this conversation that I had come to think I’d invented this parlor conversation. Hats off to the author for slipping this idea into my consciousness without my paying attention.

But it was the shooting of Danny Hansford, a 21-year staff member and rumored lover of Mr. Williams as captured in the Berendt book, that is filled with the greatest intrigue. After eight years and four trials, Williams was acquitted of murder on the grounds of self-defense. The house is home to other deaths including that of an eleven-year-old boy who fell from the roof prior to Williams’ purchase. The spike on the fence where he was found impaled is still broken. Finally, Mr. Williams himself was found in the front of the house, having died of heart failure only eight months after his legal troubles with the Hansford affair had ended. A house with so many deaths is bound to be fodder for ghost stories and many myths.

It’s impossible to know a person merely from touring their home. But the house, its owner, and the book have combined to form a great portrait of Savannah, a town that loves intrigue. The man who saved a house is captured in print, on film, and in the hearts of visitors and residents alike.

Love this somewhat dark story so close to Halloween. I will definitely read the book again.

I would’ve loved to have you as one of my history professors in college! I have always found history to be boring, except when you tell the story !!