The Idle Island of Daufuskie

I am fascinated by isolated places and the people who call those places home. What draws them there? And what makes them stay? One remote island I visited recently has a literary connection. Daufuskie Island, South Carolina, is the actual setting of Pat Conroy’s 1972 memoir The Water is Wide (in which the island is renamed Yamacraw). Conroy describes his year-long experience teaching the children on the isolated island, the relationships he built as a teacher trying to fill their educational gaps, as well as the political fights Conroy battled in his attempts to bring that education to the island. The title was inspired by his daily commute by boat to the island from Beaufort. Not a comfortable or easy task.

And neither is living on a remote island.

On this visit to Daufuskie, my mother-in-law and I hiked—okay, rode a golf cart—around the island. As we jostled along its pitted roads and breathed in pine-scented air, we came to appreciate the difficulties of leading a modern life there. There is one public ferry, one general store (very general), a few drinking establishments, several museums, a handful of churches, and smattering of artisan shops including one that demonstrates the many uses of indigo, the replacement crop for the famous sea island cotton deserted by the plantation owners after the Civil War. And back in the day, there was only one midwife on the island, a fact which must have made many pregnant women justifiably nervous. It was said that births cost $5 but funerals cost $100 – it was less expensive to come into this world than to leave it.

Curiously, there are also two abandoned golf courses on the island, failed experiments in bringing uninvited luxury to a remote place. It was an odd experience to roll through neighborhoods containing expensive, Colonial homes standing next to mothballed facilities and overgrown fairways.

Most interesting was the history of the Gullah people, descendants of the slaves, freed when the plantation owners fled as the Union troops arrived. The Gullah speak with an island brogue that resembles a creole dialect and is likely influenced by their West African heritage. (Did you know that “guber” means peanut in Gullah?) The slaves of the region likely arrived through the Port of Charleston. Due to the long history of a plantation economy, the sea islands of the Lowcountry are home to many Gullah communities. The Gullah have a strong heritage of living off the land, harvesting oysters until the Savannah River brought its chemicals, working rice fields until disease and hurricanes arrived, and fashioning baskets from the island’s sweetgrass as long as the tourists are buying.

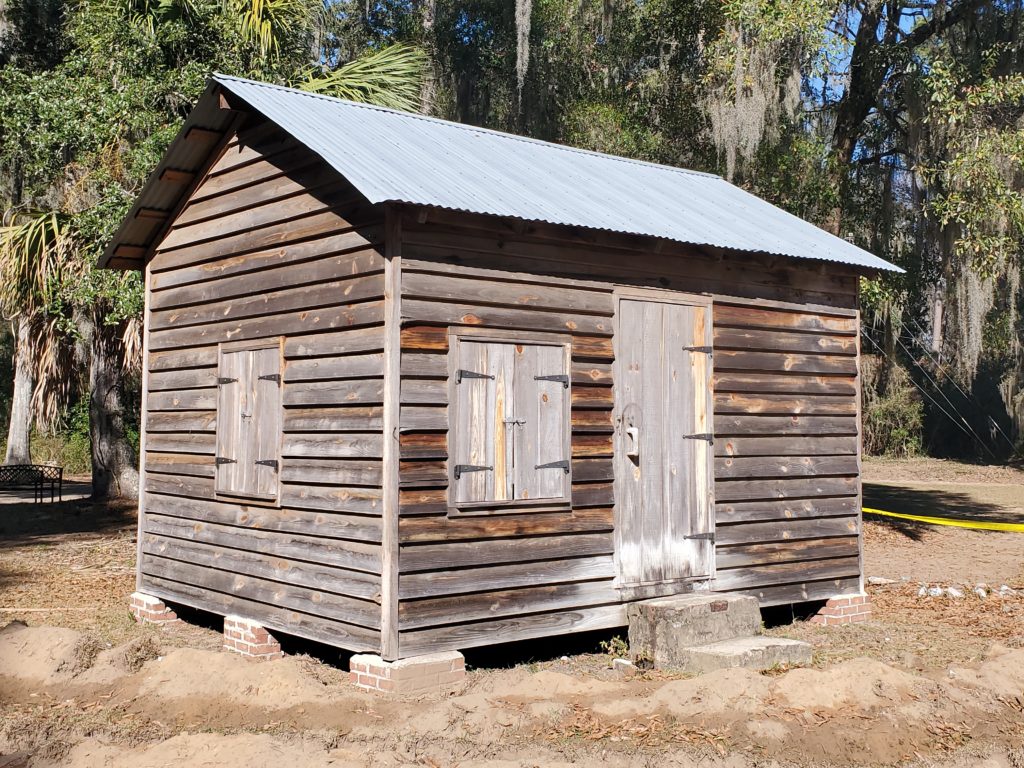

After touring a historic church with two front doors (one for each gender—oh, the silliness!), the tour guide showed us a “shout house” behind the church. This was a small shed where slaves were permitted to host their praise sessions in private. The group would move in a circle, counterclockwise, shuffling their feet, clapping, and spontaneously praying or singing aloud. Due to the nervousness these sessions brought to the plantation owners, who feared uprisings, the slaves were only permitted a few hours of praise a week. The “praise tradition” is thought to have been influential on the call-and-response tradition of the African American church as well as today’s blue and spirituals music, and even the New Orleans-style funeral processions.

Islanders are resourceful people. Dependent upon the tide or restricted by storms, they make do with what they have or can make or grow or share. There is a community spirit here that translates to neighbors relying upon each other. When someone makes a grocery run to the mainland, many orders are collected from neighbors. Our tour guide spoke of interesting activities the islanders had been called to do over the years in lieu of waiting for experts to arrive—such as tending to a beached whale or helping to recover a centuries-old indigenous canoe emerging from the marsh.

My initial impression of the island’s starkness gave way to a richness in history and culture and community, illustrating a way of life that, while unique, is also comforting in simple ways. The water may be wide, but perhaps an island so rich in history and community is not so idle after all. And the residents’ reason for staying might well be each other.

Neat story!! I love the “shout house” idea ?

So interesting , as usual! Insightful and I could visualize, with so much description available. Makes me want to visit the Island. Thank you.

The island has changed a bit since you visited. But, Pat Conroy certainly did make it famous. The Gullah people are fasinating. My mom told me so many stories of growing up in Charleston and the Gullah people were always laced into her stories. Her stories were from the 20’a and 30’s. Then in the summertime we would spend a month at the beach and would buy baskets and visit with them in the street. Love those days and the stories…thanks for bringing them back to me.

So interesting Peggy. I would love to hear some of those stories!